Niccolò Machiavelli’s the Prince

Someone once told me that Machiavelli’s little treatise, the Prince, was “baby’s first political theory.” It was a lame attempt to convince me not to read it, in leu of what, I never found out. Ultimately, I’m glad I disregarded such ignorant advice.

The Prince is probably one of the most useful, practical handbooks for vicious politicians who want to get things done. That quality alone makes it worthy of a writer’s attention.

Niccolò Machiavelli is the man of our times, and if that sounds scary to you, its because you don’t know much about Machiavelli. That’s not your fault. Cultural references to Niccolò paint him as the mastermind of tyranny. He is the eminent philosopher on cruelty; a wicked, unscrupulous, conniving historical villain whose writings helped spawn the likes of Robespierre, Stalin, and Hitler.

The English nickname for the devil, “Old Nick” is thought to derive from Niccolò. Even now, the word, Machiavellian is used to describe those who excel in the use of calculating, unprincipled tactics whether in the Boardroom, on the House Floor, or in the office. A Machiavellian man is a crafty social climber, sophisticated only so far as it helps him achieve his ambitions, maybe he’s even sociopathic?

Niccolò Machiavelli has been painted with the same broad brush that we’ve come to expect when we hear the adjective bearing his name.

But the truth is far more complicated and far more interesting. The Prince is just one small piece of the fascinating life of Niccolò Machiavelli’s life.

Niccolò, as Aristotle said of all men, was a political animal. Politics was his bread and butter, literally, it was how he paid his bills, which were always growing larger as his income grew smaller. The Prince was written as a last-ditch effort to reenter the universe of politics that he loved so much.

This effort failed so catastrophically that this stalwart defender of republican liberty became synonymous with tyranny and realpolitik.

Born in Florence in 1469 during one of the most tumultuous eras in Western history, Machiavelli, like most of his fellow Florentines, almost seemed destined to collide with greatness. He was born during a short period (1494 to 1512) when the Medici Family were deposed and the republic re-established.

Our history books tend to refer to the Renaissance as one enormous event making it seem as if it occurred simultaneously across all of Europe. The truth is, it began in Florence generations before it ever reached France and England, or even her nearby neighbors of Venice and Milan.

The world seemed to revolve around Florence in the 15th Century; for example, the Florin was the most trustworthy currency in Europe at the time and saw wide acceptance and commercial use.

But most importantly, Florence was a bastion of liberty. Florence was a republic and had been a republic since the 12th century. She wasn’t perfect, because no nation is perfect, and a citizen of modernity would have much to complain about regarding her Signoria, councils, and guilds.

Not all denizens of Florence were citizens, but the chosen few who were citizens, were granted unparalleled rights and responsibilities. In Modernity we tend to believe that liberty is do what you want. In Florence, a citizen was meant to do as they ought.

I won’t bog you down with anymore 15th Century Florentine politics, but by the time Machiavelli was born, twilight was upon the Republic of Florence and its political machine was an elaborate dance of payoffs, patronage, and surrogacy.

The Medici were expelled from Florence when, Piero, the son of Lorenzo de’ Medici the Magnificent, squandered all his father’s hard work by making a bad deal with the French. The Medici were forced to flee Florence. Florence resumed its tradition of republican government.

Machiavelli held many posts during this short period of the reassembled republic. He was a diplomat, a messenger, and even started a proper citizen-lead militia for the defense of Florence which, under his command, recaptured the rebellious city of Pisa.

But, in 1512, the Medici returned at the head of a Papal-Spanish Army and Florence crumpled. The republic was dissolved by the victors and Machiavelli was deprived of office and exiled.

A year later, Machiavelli was accused of plotting against the Medici rulers. He was seized by the government and tortured. Despite the government’s best efforts to force his arms out of their sockets in a torture method known as corda, Machiavelli never broke. If he knew who was part of the conspiracy, or even if he himself was a conspirator, he refused to say and was released a few weeks later.

He returned to his exile, and it’s hard not to assume he was a different man after that. The man who once wrote bawdy plays, Discourses on Livy (the republican version of The Prince), and corny, lewd poetry, retired to the countryside and wrote The Prince.

“Men who are anxious to win the favor of a Prince nearly always follow the custom of presenting themselves with the possessions they value most, or with things they know especially please him; so we often see princes given horses, weapons, cloth of gold, precious stones, and similar ornaments worthy of their high position.”

[The Prince, Niccolò Machiavelli, letter from Machiavelli to Lorenzo de’ Medici]

The Prince was written to help revitalize Machiavelli’s career and help him reenter the political realm.

To an urbane Florentine like Machiavelli, exile was the worse than death. It’s very difficult to categorize exile to a modern mind. Part of what makes it so terrible is the danger that the “out there” represented to people before the invention of modern firearms, inexpensive maps, and waterproof matches.

While Machiavelli spent his exile in the genteel countryside, it was far from the wild, debauched nights he’d spent with the friends of his youth and even further from the palace intrigue of Florentine politics.

He dedicated the Prince to Giuliano di Lorenzo de’ Medici, the third son of Lorenzo de’ Medici the Magnificent, in hopes of gaining entry to the old, but newly reestablished, halls of power.

The book would go unpublished and, presumably, unread, until after Machiavelli’s death.

During the Middle Ages and Renaissance, humanist writers were obsessed with writing books and philosophizing on “what makes a good prince.” The question became a genre of itself, known as “Mirrors for Princes” and usually focused on how a prince ought to be educated, what virtues make for a good leader, etcetera.

Machiavelli simply took that idea to its natural conclusion, asking instead, “how does one become a prince” and “how does a prince keep his power?”

While his contemporaries wrote treatises on the best Christian virtues and behaviors to instill in a young king-in-waiting, Machiavelli’s work can be summed up easily as: be a lion, unless you must be a fox.

“So, as a prince is forced to know how to act like a beast, he must learn from the fox and the lion; because the lion is defenseless against traps and a fox is defenseless against wolves. Therefore, one must be a fox in order to recognize traps, and a lion to frighten off the wolves. Those who simply act like lions are stupid.”

[The Prince, Niccolò Machiavelli, Chapter XVIII: How princes should keep their word]

“Those who simply act like lions are stupid.” A lot of writers would do well to heed this line.

One of my least favorite tropes is the over-the-top tyrannical king who rules his people with a bloody iron fist.

Part of my problem with trope of the Tyrannical King is that it is often misused. The writer makes their Tyrant King viciously murder friend and foe alike, they surround him with sycophants and bootlicks, and never consider (beyond the needs of their protagonists and plot) how these actions might affect the ruling ability of a king.

Machiavelli has an entire chapter about those who win their power by crime. He uses an example from antiquity, Agathocles, a man who through treachery and crime, rose to become the ruler of Syracuse. Of this tyrannical king, Machiavelli said this:

“It cannot be called virtue to kill one’s fellow-citizens, betray one’s friends, be without faith, without pity, and without religion; by these methods one may indeed gain power, but not glory. For if the virtues of Agathocles in braving and overcoming perils, and his greatness of soul in supporting and surmounting obstacles be considered, one sees no reason for holding him inferior to any of the most renowned captains. Nevertheless his barbarous cruelty and inhumanity, together with his countless atrocities, do not permit of his being named among the most famous men. We cannot attribute to fortune or virtue that which he achieved without either.”

[The Prince, Niccolò Machiavelli, Chapter VIII: Those who come to power by crime]

The limp, ill-used Tyrant King is a villain, he does villainous things. He tortures little girls for fun and kicks puppies when he’s bored, his life is debauched with wine, women, and blood. He is evil, he is a tyrant and that is the extent of his character. His wickedness stems from the writer’s need to contrast the goodness of their hero with the malfeasance of their villain.

But one moment of thought and a writer may realize that a king who lets his troops slaughter villages, rape townspeople, and burn farms will soon find his army starving. Starving solider soon turn on that king. This idiot lion, this misused trope, has the potential to be interesting, but much like the tyrant’s strategy, the story is not sustainable and it’s not interesting.

Instead, writers should heed what Machiavelli says next:

“Some may wonder how it came about that Agathocles, and others like him, could, after infinite treachery and cruelty, live secure for many years in their country and defend themselves from external enemies without being conspired against by their subjects…

I believe this arises from the cruelties being exploited well or badly. Well committed may be called those (if it is permissible to use the word well of evil) which are perpetrated once for the need of securing one’s self, and which afterwards are not persisted in, but are exchanged for measures as useful to the subjects as possible. Cruelties ill committed are those which, although at first few, increase rather than diminish with time.”

[The Prince, Niccolò Machiavelli, Chapter VIII: Those who come to power by crime]

Well-committed cruelty—what a concept! Imagine a villain who wins loyalty and love like a hero. Now there’s a story I’d love to read.

“It is to be noted, that in taking a state the conqueror must arrange to commit all his cruelties at once, so as not to have to recur to them every day, and as to be able, by not making fresh changes, to reassure people and win them over by benefiting them.”

[The Prince, Niccolò Machiavelli, Chapter VIII: Those who come to power by crime]

The chapter concludes, warning would-be tyrants that those who fail to act decisively and craftily (like a lion or fox), should be prepared to always keep a knife in their hands at the ready, because someone will always be trying to shove one into their back.

“…a prince must live with his subjects in such a way that no accident of good or evil fortune can deflect him from his course…”

[The Prince, Niccolò Machiavelli, Chapter VIII: Those who come to power by crime]

Eyes on the prize. Don’t let innate cruelty get in the way of the goal. If you want to write a believable, canny, terrifying Tyrant King, I suggest you take Machiavelli’s advice.

Most of the Prince is like this, salacious advice for how to be cruel without being too cruel. But that’s the easy was to read it. There are some historians and philosophers, like Erica Benner in her book Be Like the Fox, who believes that Machiavelli’s intentions with the Prince were far more noble and far more underhanded than we think.

What if Machiavelli was writing a book to tell the liberty-minded what to expect and how to treat tyrants? What if Machiavelli’s Prince is actually a handbook for heroes?

I’ll admit that the evidence is found more in the life and other writing of Machiavelli, but within the Prince there are some interesting passages regarding republican government and how an elected Prince can hold onto the power given him by the people.

“A man who becomes prince by favor of the people find himself standing alone, and he has near him either no one or very few not prepared to take orders…

The people are more honest in their intentions than the nobles are, because the latter want to oppress the people, whereas they only want not to be oppressed…

…it is necessary for a prince to have the friendship of the people; otherwise he has no remedy in times of adversity.”

[The Prince, Niccolò Machiavelli, Chapter IX: The constitutional principality]

Later on, Machiavelli goes on to encourage princes to start citizen-militias! Common wisdom states that a tyrant who arms his civilians will soon find those arms used against him.

Why would a man believed to be as evil as Machiavelli, a supporter of cruel tyrants, advise those tyrants that you can’t have good laws without good arms and that with good arms, good laws follow?

Whether you’re writing heroes or villains, Machiavelli’s little book on Princedom is excellent primer on practical politics. Your tyrants will become savvy, cruel, and clever. Your heroes will be wise, cunning, and vicious. You’ll write lions who easily transform into foxes.

Niccolò Machiavelli’s the Prince is an absolute must read for writers. It’s short, it’s punchy, and its one of my favorite books by one of my favorite historical figures.

I like the Penguin Classics version, translated by George Bull. It’s very readable, dispenses with some of the clunky phrasing, and includes historical notes in the back. However, it is also available from the University of Baltimore for free here. I used both translations for the quotes above.

[More Writers Must Read]

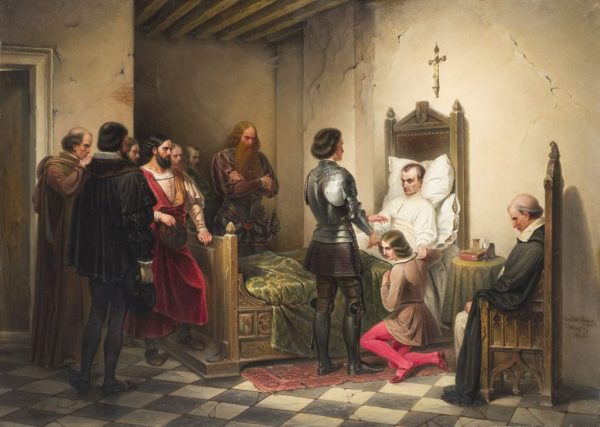

Above: Morte di Niccolò Machiavelli. Cesare Felice Giorgio Dell’Acqua (22 July 1821 – 16 February 1905), Italian Painter. Oil on canvas. Housed at the Revoltella Museum, Trieste, Italy.