The trope is called “meet-cute.” I hate the name of this trope. I can’t really tell you why I don’t like the name, maybe it’s because I really just think it’s romance lampshading under a different name? Either way, I prefer the Chinese/Japanese concept of the red string of fate.

However, I’m not going to focus on the many variants of this specific trope. I’m really looking for the barebones, basic, down-to-the-studs archetype. For the purpose of this essay, we’re going to call this plot device the “fated meeting.”

The highlighted action of this trope, as we’ll see in the readings, is change. The meeting at the well is a vehicle for alteration of state, whether physical, mental, and/or spiritual.

There are three fated meetings I want to dissect. Two from the Old Testament Book of Genesis, and the final from the New Testament Gospel of John.

Rebecca at the well

We’ll start with Genesis 24, the Marriage of Isaac and Rebecca. Here’s a quick summary of the events leading up to the fated meeting.

Shortly after the death of his wife, Sarah, Abraham calls a servant to his side and commands him to swear an oath that if he [Abraham] should die, the servant will see to it that his son, Isaac, does not marry a foreign woman. Abraham asks the servant to “go to my country and to my kindred and take a wife for my son Isaac.” [Gen 24:4 RSV-2CE]

After some reasonable negotiations, the servant swears to go to the city of Nahor in Mesopotamia. He takes camels laden with gifts for the future bride and her family. When the servant makes it to the city, he finds a well and makes the camels lay down in the evening. Evening is a time when the women of the city come and fetch water for their households.

The servant then prays:

12 O Lord the God of my master Abraham, meet me to day, I beseech thee, and shew kindness to my master Abraham. 13 Behold I stand nigh the spring of water, and the daughters of the inhabitants of this city will come out to draw water.14 Now, therefore, the maid to whom I shall say: Let down thy pitcher that I may drink: and she shall answer, Drink, and I will give thy camels drink also: let it be the same whom thou hast provided for thy servant Isaac: and by this I shall understand, that thou hast shewn kindness to my master. 15 He had not yet ended these words within himself, and behold Rebecca came out, the daughter of Bathuel.

[DRV 24:12-15]

We get a small description of Rebecca, she is “exceedingly comely” and a “beautiful virgin.” She passes the servant and fills up her water jar. On her way back up the road to home, Abraham’s servant runs out to meet her:

17 And the servant ran to meet her, and said: Give me a little water to drink of thy pitcher. 18 And she answered: Drink, my lord. And quickly she let down the pitcher upon her arm, and gave him drink. 19 And when he had drunk, she said: I will draw water for thy camels also, till they all drink. 20 And pouring out the pitcher into the troughs, she ran back to the well to draw water: and having drawn she gave to all the camels.

[DRV 24:17-20]

Hauling water is hard work, what Rebecca is doing here is extremely generous. Now, certainly, Rebecca sees these camels laden with gifts and, being a perceptive woman, would know that helping this man could be to her benefit. It is possible to be both simultaneously generous and shrewd. There are no other women mentioned in this passage, but we should assume them there and all but Rebecca are passing the servant by.

Fetching water from the well is a social affair. Women go in groups. It’s a time for gossip and giggles. While the other women move on, heading home before it gets dark, Rebecca fills the trough for the camels to drink. She may even be risking her reputation here, it’s not normal for a woman to be alone with a strange man and in ancient societies, it was a sign of infidelity, regardless if sex occurred or not.

21 But he [the servant] musing beheld her with silence, desirous to know whether the Lord had made his journey prosperous or not. 22 And after that the camels had drunk, the man took out golden earrings, weighing two sicles: and as many bracelets of ten sicles weight.23 And he said to her: Whose daughter art thou? tell me: is there any place in thy father’s house to lodge? 24 And she answered: I am the daughter of Bathuel, the son of Melcha, whom she bore to Nachor. 25 And she said moreover to him: We have good store of both straw and hay, and a large place to lodge in.26 The man bowed himself down, and adored the Lord.

[DRV 24:21-26]

The servant muses, watching her, amazed that he might have fulfilled his master’s wishes. Once he knows who she is, he adores the Lord for his good fortune. Rebecca returns to her home and the servant follows. He is brought into the house and offered food and lodging, but the servant will not eat until he has told his story:

45 And whilst I pondered these things secretly with myself, Rebecca appeared coming with a pitcher, which she carried on her shoulder: and she went down to the well and drew water. And I said to her: Give me a little to drink. 46 And she speedily let down the pitcher from her shoulder, and said to me: Both drink thou, and to thy camels I will give drink. I drank, and she watered the camels.

[DRV 24:45-46]

I want to note here that it’s a common structural trope for the Israelites to repeat things. They only repeat things that are very, very important. That’s why we’re getting a repeated play-by-play of the event we just read.

This is for practical reasons. Most people at the time couldn’t read, repeating something in a slightly different way helps them to remember that which is important. There is also a poetic quality to it, after all, Genesis is a work of Hebrew poetry.

Once the servant finishes his tale, he receives his answer:

50 And Laban and Bathuel answered: The word hath proceeded from the Lord, we cannot speak any other thing to thee but his pleasure. 51 Behold Rebecca is before thee, take her and go thy way, and let her be the wife of thy master’s son, as the Lord hath spoken.

[DRV 24:50-51]

Rejoicing, the servant gives out the gifts to Rebecca, clothing her in fine raiment, silver, and jewels. He gives gifts to Rebecca’s brother, Laban, and her mother. He and the men with him eat and drink and celebrate for three days. After three days they ask to return to Abraham in the land of Canaan. There is resistance from Laban and his mother at first, so they ask Rebecca what she wants. Rebecca says: “I will go.”

61 So Rebecca and her maids, being set upon camels, followed the man: who with speed returned to his master. 62 At the same time Isaac was walking along the way to the well which is called Of the living and the seeing: for he dwelt in the south country. 63 And he was gone forth to meditate in the field, the day being now well spent: and when he had lifted up his eyes, he saw camels coming afar off.

64 Rebecca also, when she saw Isaac, lighted off the camel, 65 And said to the servant: Who is that man who cometh towards us along the field? And he said to her: That man is my master. But she quickly took her cloak, and covered herself.

66 And the servant told Isaac all that he had done.67 Who brought her into the tent of Sara his mother, and took her to wife: and he loved her so much, that it moderated the sorrow which was occasioned by his mother’s death.

[DRV 24:61-67]

One suspects that during their travels and during the three days spent in Nahor, the servant has been telling Rebecca stories about Isaac. Her willingness to go to Canaan after three days suggest that she is already interested in Isaac and once Isaac hears the stories of Rebecca, he takes her as his wife and “loved her.”

There a lots of women in the Bible, not all of them are strong like Deborah, or generous like Rebecca, many of them are misused by the men around them, all of them are sinners. Many are mentioned in genealogies and then never mentioned again.

Rebecca stands above them all, because Rebecca was loved. Even David did not “love” Bathsheba. Jacob did not love Leah the way he loved Rachel. While disorder always makes its way into the story, it seems that this fated meeting works out as the trope intends.

Jacob meets Rachel

The second fated meeting is between Jacob and Rachel. Jacob is the son of Isaac and Rebecca. He has fled his father and brother at the behest of his mother. Jacob is a cheater. He is his mother’s favorite child while his brother Esau is Isaac’s favorite. Using trickery, (his mother’s idea, she is a shrewd woman), Jacob steals a blessing meant for Esau from his aged and blind father.

This isn’t the first time Jacob has pulled something like this. Jacob and Esau are twins, which is a topic for later discussion, just know that their relationship is contentious to the point that Jacob fears the wrath of his brother and runs away from home. This is, of course, a little micro-example of the hero’s journey, but let’s remain focused on the well.

Jacob journeys into the east, where his mother’s kin dwell. He stops at the well where several shepherds are waiting for the rest of the flocks to be gathered so that they can water the sheep. There is a large stone over the well’s mouth, suggesting that the shepherds must wait for the other shepherds in order to move the stone. Jacob asks them if they know his kinsman, Laban:

“Yes,” they replied, “and here is his daughter Rachel, coming with the sheep.” 7 He [Jacob] said, “Look, it is still broad daylight; it is not time for the animals to be gathered together. Water the sheep, and go, pasture them.” 8 But they said, “We cannot until all the flocks are gathered together, and the stone is rolled from the mouth of the well; then we water the sheep.”

[RSV-CE 29:6-8]

I suspect Jacob hopes to move the shepherds along so that he can speak to Rachel alone. In the end, he rolls the stone out of the way. He then waters the sheep under Rachel’s care.

Then Jacob kissed Rachel, and wept aloud. 12 And Jacob told Rachel that he was her father’s kinsman, and that he was Rebekah’s [Rebecca] son; and she ran and told her father.

13 When Laban heard the news about his sister’s son Jacob, he ran to meet him; he embraced him and kissed him, and brought him to his house. Jacob told Laban all these things, 14 and Laban said to him, “Surely you are my bone and my flesh!” And he stayed with him a month.

[RSV-CE 29:11-14]

Laban offers to give Jacob wages for his work.

16 Now Laban had two daughters; the name of the elder was Leah, and the name of the younger was Rachel. 17 Leah’s eyes were lovely,[b] and Rachel was graceful and beautiful. 18 Jacob loved Rachel; so he said, “I will serve you seven years for your younger daughter Rachel.” 19 Laban said, “It is better that I give her to you than that I should give her to any other man; stay with me.” 20 So Jacob served seven years for Rachel, and they seemed to him but a few days because of the love he had for her.

[RSV-CE 29:16-20]

Rachel, like Rebecca, is loved. Jacob works diligently for his Uncle, increasing Laban’s wealth and flocks with the expectation that he will be married to Rachel at the end of seven years.

But something happens. It’s Leah, Rachel’s sister, who Jacob ends up married to. In the morning, when the deception is seen, Jacob is outraged.

And Jacob said to Laban, “What is this you have done to me? Did I not serve with you for Rachel? Why then have you deceived me?” 26 Laban said, “This is not done in our country—giving the younger before the firstborn. 27 Complete the week of this one, and we will give you the other also in return for serving me another seven years.” 28 Jacob did so, and completed her week; then Laban gave him his daughter Rachel as a wife. 29 (Laban gave his maid Bilhah to his daughter Rachel to be her maid.) 30 So Jacob went in to Rachel also, and he loved Rachel more than Leah. He served Laban[c] for another seven years.

[RSV-CE 29:25-30]

What goes around, comes around. But all this trickery is to the determent of the characters involved. Leah is aware of her position in Jacob’s household. Rachel is the favored wife, and there is nothing more painful than knowing that you play the consolation prize in someone else’s love story.

31 When the Lord saw that Leah was unloved, he opened her womb; but Rachel was barren. 32 Leah conceived and bore a son, and she named him Reuben;[d] for she said, “Because the Lord has looked on my affliction; surely now my husband will love me.”

[RSV-CE 29:31-32]

“Surely now my husband will love me.” Meet-cute indeed. Human relationships are messy things. And while the story of Jacob’s immediate family has a happy ending, the rivalry between Leah and Rachel, made possible by Jacob’s clear favoritism, leads to his sons conspiring to murder their brother, Joseph.

The Samaritan Woman

Our final fated meeting is set in Samaria, near the city of Sichar. Jesus of Nazareth stops at a well dug by Jacob. It’s noon and Jesus is tired and thirsty. There is no one around, he sits by the well, and sees a Samaritan woman, coming, alone in the heat of the day, not the coolness of evening, with the other women.

7 A Samaritan woman came to draw water, and Jesus said to her, “Give me a drink.” 8 (His disciples had gone to the city to buy food.) 9 The Samaritan woman said to him, “How is it that you, a Jew, ask a drink of me, a woman of Samaria?”

[RSV-CE John 4:7-9]

Its important to know that Samaritans and Jews do not get along. The Samaritans hold to only the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, the Pentateuch, that is Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy and exclude the rest of the Prophets. The Jews held that the Samaritans do not properly worship God and the Samaritans held that the Jews don’t properly worship God. The Jews reverence Mount Zion and the Samaritans reverence Mount Gerizim. The Samaritans are the ancestors of foreign settlers in Israel during the Exilic Period. There is no love between these two people.

By the traditions and biases of his people, Jesus shouldn’t be speaking to this woman, let alone asking her for a drink. But Jesus is the hero par excellence. He is on his hero’s journey and he will not be stopped by archaic rules and prejudices. He speaks to her:

10 Jesus answered her, “If you knew the gift of God, and who it is that is saying to you, ‘Give me a drink,’ you would have asked him, and he would have given you living water.” 11 The woman said to him, “Sir, you have no bucket, and the well is deep. Where do you get that living water? 12 Are you greater than our ancestor Jacob, who gave us the well, and with his sons and his flocks drank from it?” 13 Jesus said to her, “Everyone who drinks of this water will be thirsty again, 14 but those who drink of the water that I will give them will never be thirsty. The water that I will give will become in them a spring of water gushing up to eternal life.” 15 The woman said to him, “Sir, give me this water, so that I may never be thirsty or have to keep coming here to draw water.”

[RSV-CE John 4:10-15]

This event concludes with Jesus telling the woman to go and get her husband and come back. She tells him that she doesn’t have a husband and Jesus says “You are right in saying, ‘I have no husband’; for you have had five husbands, and the one you have now is not your husband.”

The Samaritan woman came to the well alone. She was alone with a strange man. She’s been living with a man who is not her husband. She is an absolute outcast from her society. And Jesus, being the Messiah, knows this. He speaks to her anyway. A good hero is not moved from his quest, not for anything. At times he may doubt it, he may retreat to the desert for clarity, but he should never step off it—that is the path to villainy.

The woman returns to the city to tell the people what she has been told.

28 Then the woman left her water jar and went back to the city. She said to the people, 29 “Come and see a man who told me everything I have ever done! He cannot be the Messiah,[e] can he?” 30 They left the city and were on their way to him.

[RSV-CE John 4:28-30]

The people see Jesus and listen to him and they believe that he is the long-awaited Messiah. This is in sharp contrast to his own people, who do not believe in him.

Well, Well, Well

These are three very similar, very different fated meetings. As we view these stories as stories, we see the well as a plot contrivance. Don’t take “plot contrivance” negatively. It’s a device that allows writers to get the plot moving. The well is a meeting place, an ancient singles bar, if you will.

Its no different from a character missing the bus and meeting his future wife at the stop. He’s never late and she’s always late. She’s beautiful, but he can’t stand how she never in a hurry. He’s handsome, but she can’t keep up with his fast-paced lifestyle. For all their disagreements and future conflict, missing that bus was the best thing that ever happened to them.

What makes a plot contrivance effective as a storytelling element is the ultimate symbolism behind the device in use. Let’s continue with the bus metaphor.

Let’s say that the man loves timeliness, he loves to be orderly and well-kept. He is “married” to his work. He’s never missed a day and he’s never been late. But after a hard night of working on his company’s latest project, he fails to properly set his alarm. He lives in a city where having a car is impractical. Missing the bus on the morning of an important work meeting is catastrophic to him.

The woman is laid back and calm. She bounces from job to job because she’s easily bored. She’s currently a waitress so missing the bus isn’t a huge deal, she’s more than happy to move onto the next gig. Missing the bus is just another opportunity for her to roll with the punches. Seeing how uptight the man is, she offers to help him navigate the subway. They get lost instead and it’s the best worst day of the man’s life. There are consequences of course.

For the man, the bus is a symbol of his fast-pace, highly regimented life. Forgetting to set his alarm shows us how much of his life is consumed in work. In his exhausted state, he fails to set it right. Our leading lady is the catalyst to the disorders that occur with missing such an important work event. She has also become the source of his happiness. The tension between those two symbols—chaos and joy—is the story people want to read.

So, what’s in a well?

I don’t think I need to impart the importance of water to a desert people. Men guarded their wells with viciousness—to steal from a tribe’s well was to sign a death warrant. You are literally stealing that tribe’s life, water they need to sustain their flocks and their families. Losing a well in war could destroy a tribe. Cities grew up around wells so that this source of life could be protected by the tribal group.

Women go together to the well, they share gossip, advice, and jokes. They play matchmaker for each other, discuss their children, their husbands, and family problems. It’s at the well that they go about the natural and normal business of running a household and therefore, civilization.

A well is a place of refreshment, where the tired and thirty rest in the shade and the cool waters. It’s a miniature oasis, a small sip of paradise to come.

Rebecca drew water from the well for the Abraham’s servant. She put aside her family duties to help a stranger, watering his camels and refreshing him. She is generous, but sees the chance to build her own household, increasing the wealth and connections of her family. She is going about the important business of civilization, selflessly providing the sweat of her brow. Before Rebecca was even born, it said to Abraham that God would make a great multitude of him. His descendants would number the stars.

It’s women like Rebecca, who draw out of themselves, the life sustaining water that nourishes a tribe. The well is a plot contrivance, a place to meet, an active symbol of what is occurring in the life of these characters. She’s a girl who goes from her father’s house to work and run her husband’s house. Our man above misses the bus because he’s missing out on life.

Rachel too is going about this important work. She is caring for her father’s flocks and all that entails. Then, Jacob comes and does the same, increasing and caring for Laban’s household and wealth. For his work, he is tricked—but the trick is a direct result of his untrustworthiness. Wells can be deep and even treacherous.

A stone covers the well where Jacob and Rachel met, perhaps to keep people and animals from falling in and drowning? Jacob rolled away the stone only to fall in. Stuck with unhappy, quarrelsome wives, no doubt he felt like he was drowning.

Our man who missed the bus must eventually face the consequences of missing work, marking a massive change in the relationship between the man and the woman. He must count the cost of meeting her.

Then comes Jesus, the Messiah. He knows the depths of every well. He knows a calm surface hides a muddy bottom. The Samaritan woman was alone at the well, she was cast out from society for her sins. He asks her for a drink—breaking all propriety—because she is worth something, even if she doesn’t feel worthy.

The living water he offers her is spiritual. It will clean away everything, even the sins she commits in the future.

Water is a source of life, we drink it, but we bathe in it too. Water makes us clean, it refreshes the hot and tired, when heated it warms the heart. Jesus has come into this woman’s life and given her a taste of that life-giving water; he changes how she sees herself and the world around her.

Our man who missed the bus has a met a wild girl who arouses his love and takes him on an adventure. Work won’t satisfy him ever again.

I said above that I dislike the name “meet-cute.” I still do. But this trope is a powerful one. Meeting in a silly or cute or awkward situation is a plot contrivance, but that is how we get characters to meet. In order to move the plot or get the message across we must get the characters to come together because in meeting they make change.

Tropes are anchors. As readers, we latch on to them, seeking their familiar shapes, but we allow ourselves to be surprised by the colors and the little details that differ with every story. As writers, that is what we must do.

Take a trope, color outside the lines, make it your trope—pretend like no one has ever done this before and own it. We’ve got three radically different meaning out of these Biblical fated meetings, three different changes. Never assume a trope is worthless because it’s been done before. It’s your characters, their personality and circumstances, your details and written style that make the story.

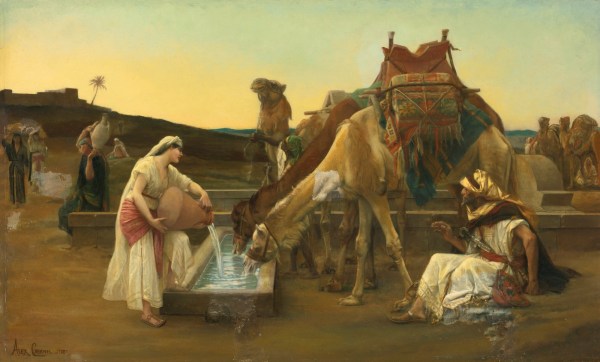

Above: Rebecca et Eliézer. Alexandre Cabanel, 28 September 1823 – 23 January 1889. French Painter. Oil on canvas. In private collection.