He was seventeen years old and already wore the red. Cardinal Raffaele Sansoni Riario was the grand-nephew of Pope Sixtus IV. Although still studying canon law in Pisa, he had been invested by the Holy Father with the diplomatic powers of a Papal Legate. It was under the Pope’s authority that he was in Florence.

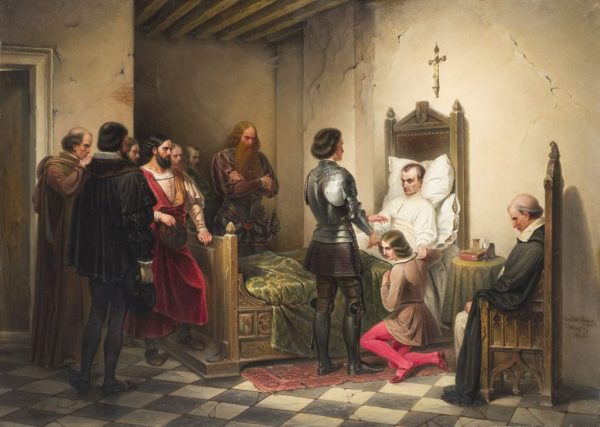

On Sunday, April 26th 1478, the young Cardinal was celebrating High Mass at the Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Flower when violence splattered blood across the sacred floors of the Duomo.

Terrified and confused, the youth threw himself behind the altar and prayed for God’s protection amidst the screams of women, children, and the outraged shouts of “here traitor!”

Not more than thirty yards from where the Host had been elevated, Giuliano de’ Medici was stabbed nineteen times by Bernardo Baroncelli and Francesco de’ Pazzi. Closer to the altar, a pair of Priests attacked Giuliano’s older brother, Lorenzo.

Lorenzo’s employee and close friend, Francesco Nori stepped between him and his attackers, sparing Lorenzo’s life at the cost of his own. Another servant fought off one of the Priests and was wounded. Protected by his friends and servants, Lorenzo escaped into the sacristy with nothing but a small wound under his right ear.

Trapped in the sacristy of the Cathedral, Lorenzo, known as the Magnificent, had no idea that his brother was dead.

Within just a few minutes the marble mosaic floors of the Florentine Cathedral were slick red with blood.

It was just the beginning. The bloodshed would extend for three days, overtaking the city of Florence in an orgy of violence. Hundreds would be killed in that three-day period, but the retribution for the death of Giuliano de’ Medici and the attempted assassination of Lorenzo the Magnificent would span years.

The glory of the Florentine Republic had long been waning by the time the Pazzi made their ill-fated attempt on the Medici’s lives. Although it would resurge from time to time, the Republic was on its last legs. Lorenzo de’ Medici, a man as brilliant as he was shrewd, would not waste the opportunities that his brother’s sacrifice revealed.

When the Lord Priors or, Signoria, Florence’s top ruling council, heard of the violence they immediately called in the Eight—an inquisitorial office made for rooting out and prosecuting political crimes. Prisoners were taken, including the men who murdered Giuliano and attempted to murder Lorenzo. Laws were suspended and emergency powers were delegated. Justice would be swift and cruel.

Foreign mercenaries who had been brought into the city were immediately massacred, thrown out the windows of the Palazzo della Signoria which they had occupied in the attempted coup.

The first conspirator to hang was Jacopo Bracciolini. A rope was put around his neck and he was thrown out the top window of the Palazzo overlooking the Piazza della Signoria. Two hours later, he was joined by Francesco de’ Pazzi, he had been the one to shout “here, traitor!” and in his fury to slay Guiliano, had stabbed himself in the thigh.

Then, shockingly, the Archbishop of Pisa, Francesco Salviati was hung, as well as an unidentified cleric. More men would hang from the Palazzo windows that day.

In the words of Niccolo Machiavelli, who was a child at the time of the Pazzi Conspiracy, there were “so many deaths that the streets were filled with the parts of men.” (pg. 128)

The violence began to slow only when someone realized that the mob violence could easily turn on the government elite, especially because the 1470s had been a time of famine. But that didn’t mean that Lorenzo’s vengeance was over.

Cause and Effect

I make no secrets about my fascination with Florentine politics. It started with Dante and a desire to better understand his Divine Comedy by studying the man and the world he belonged to. It turned into a mild obsession that may or may not have contributed to my Conversion.

While the plots, schemes, and drama are mesmerizing, what makes Medieval and Renaissance Florence such a captivating study is the people. Florence is one of those strange places in history where great men all seemed to promulgate.

From Dante to Petrarch to Boccacio and Michelangelo, Donatello, Da Vinci, Botticelli, Giotto, Machiavelli, Brunelleschi, Savonarola, and Amerigo Vespucci, America’s namesake—yes, that’s right. Florence’s influence even endowed the United States with its name. The Renaissance began in Florence and was bankrolled by Florentine gold and Florentine blood.

But why should a writer care? Why should I recommend April Blood, by Lauro Martines?

On a very basic level, a story is about cause and effect. Something happens and a character must commit to an action in response to that event. A very good story layers causes and effects on top of each other. Soon, a story stars looking like ripple in a pond.

I can think of no better place to meditate on this fundamental building block than in 16th Century Florence. April Blood, like any good tale, is a story about cause and effect. But unlike a novel, the characters and the plot were real. Every man involved in the Pazzi Conspiracy, from the victims to the conspirators, had a reason to act the way they did. Whether those reasons are justifiable is irrelevant. This complex web of money, family, and politics, merely proves my point.

Complex Characters

Lorenzo de’ Medici was raised to inherit his father’s patrimony. That patrimony was “the head and heart of a tightening oligarchy,” a tangled web of banking interests, political machinations, and marriage alliances (April Blood, pg. 88).

Lorenzo was 20 when a delegation of Florentine politicians offered him the reins of the state. Which, he took. The power that his grandfather, Cosimo, had gathered was so weighty that, even if the Medici had wanted too, they would not have been able to set it down without great personal risk.

“Lorenzo…aimed to hold power like his grandfather Cosimo, ‘with as much civility as he could manage’, which of course meant vote-rigging and ‘handling’ (that is, fixing) the purses for high office.”

April Blood pg. 95

Purse handling is an unfamiliar term for those unacquainted with Florentine Republicanism. In Florence, the Signoria, a council of nine men, led by the Gonfaloniere were selected randomly for two-month terms. By “handling the purse,” Lorenzo ensured that the random officials selected for office were the correct random officials.

Under the control of the Gonfaloniere and the Signoria were several different councils and committees—the Cento, the dreaded Eight, the Committee of War, etc.

Lorenzo indirectly controlled the Florentine government by ensuring that people friendly to the Medici were in power. This didn’t always work, so, naturally, after loosing control of the Signoria, Lorenzo resolved to ensure that it didn’t happen again. The moment Lorenzo regained control of the government; he pushed forth a series of:

“beautifully- orchestrated ‘reforms’ [that] had been a matter of timing, numbers, disinformation, intimidation, bribery, and electoral machinations. This was Renaissance statecraft as art: the paradigm of what it was to rule by ‘civil’ and ‘constitutional’ means in Medicean Florence.” April Blood, pg. 96

Somewhere along the line, Lorenzo, who was related to the Pazzi family through his sister’s marriage to Guglielmo de’ Pazzi, began to sense the ambitions of the Pazzi Family, particularly, those of Jacopo, the Pazzi Patriarch. With his control over the purse, Lorenzo began to halt their political advancements, barring the Pazzi from entry into high political office.

We may never know what the final straw was for the Pazzi family, all of them seemed to have had their own motivations, but one motive does come into sharp focus. In an act of pure spite, Lorenzo, against even the advice of his most trusted advisors including Guiliano, pushed forth a law that deprived daughters of major inheritances if they had no brothers and were flanked by one of more male cousins.

This law purposefully disinherited Beatice Borromei, the wife of Giovanni de’ Pazzi and barred the Pazzi from taking control of her large fortune.

Of course, this move was not done in a vacuum. Lorenzo forced that bill through because the Pazzi had been disrupting his imperialistic diplomatic plans.

The Pazzi, against Florentine (read: Lorenzo’s) diplomatic program, fronted Pope Sixtus IV a loan so that he could purchase a piece of land for his nephew, land that Lorenzo had wanted for Florence. To punish Lorenzo for not lending him money, Sixtus removed the Medici bank as Papal Bakers and gave the contract to the Pazzi bank.

To make matters worse, the Pope then elevated Francesco Salviati to the Archbishopric of Pisa. Pisa, at the time, belonged to Florence, and Salviati was a Pazzi relative. Lorenzo had good reason to believe that Salviati would be elevated to Cardinal and he was furious that he had not been given a say in the selection.

But that’s just the master of realpolitik.

“He was to have two souls always, two sides: one for literature and the other for callous action in the world.”

April Blood, pg. 91

I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that without Lorenzo the Magnificent, the Renaissance might have gone very different. Although he was a poet himself, his most important contribution to the West was his patronage.

The network of patronage went beyond bankrolling some of the greatest artists the world has ever seen (Leonardo de Vinci, Michealangelo, Sandro Botticelli). He was instrumental in connecting artists and earning them commissions. I think it’s safe to say that Lorenzo spent all this capital (social and monetary) out of a pure love of art.

But Lorenzo was not the only Patron of the Arts in Italy. There was one man in Rome to whom all Christendom owed their allegiance.

He was born Francesco della Rovere and entered into Church life as a Franciscan. When he was elected Pope, he took the name Sixtus IV. He would complete three mighty achievements: the construction of the Sistine Chapel, the creation of the Vatican Library, and the founding of the Spanish Inquisition. But even those accomplishments paled in comparison to his nepotism.

Sixtus IV raised nepotism to an art form. He was surrounded by nephews, nieces, grand-nephews, brothers, etc. Cardinal Raffaele Sansoni Riario the seventeen-year-old boy mentioned above, was his grand-nephew! The land that he secured with a Pazzi loan was for his other nephew, Girolamo Riario.

It would take more ink and time to list every relative that Sixtus IV raised and enriched. The two mentioned above are merely the most important for the purpose of this essay.

Girlamo Riario, along with the Archbishop of Pisa, were probably the originators of the plot to kill the Medici brothers. Perhaps sensing an opportunity to tighten his nepotic hold on Italy, the Holy Father agreed that Florence needed a change in government.

“His Holiness definitely wants and change in the government in Florence, but without anyone’s death…His Holiness said to me I want no death not for any reason. It is not part of our office to consent to any person’s death, and though Lorenzo is a scoundrel and behaves badly with us, yet on no account would I wish to see him dead…I tell you I want no man dead but a change in government, this yes.” April Blood, pg. 158

Here was a man devoted to his family while simultaneously committed to the Franciscan order. He had taken a vow of personal poverty, yet he poured out money like water to build one of the most glorious devotions to God. He was the Pope, the Vicar of Christ, the Prime Minster of Christ’s Kingdom on earth, yet he connived to see men murdered—surely, he knew what he was saying? He could not have been that naive. A man does not become Pope by being naïve.

If You’re Going to Kill a King

It goes without saying that if you plot an assassination, you better not fail. The April plot was more than just a disgruntled family looking for vengeance. It was a cadre of angry, ambitious men ranging from a banker, to an archbishop, to a duke, to a king.

Lorenzo learned the details of the plot, including Pope Sixtus IV’s involvement, through the confession of one of its conspirators—Giovan Battista, Count of Montesecco. The Count was a mercenary

Date eight days after the attempted assignation of Lorenzo, Giovan Battista penned his confession, pinning the plan on three major players: Archbishop Salviati of Pisa, Francesco de’ Pazzi, and Count Girolamo Riario, the Pope’s nephew. His confession went on to implicate the Holy Father, the Duke of Urbino, and the King of Naples.

Lorenzo hardly needed the confession to know that the Pope was involved. Afterall, his would-be killers were hidden among the courtiers of his grand-nephew, Cardinal Raffaele Sansoni Riario! I doubt the seventeen-year-old had any idea that his train of servitors was carefully choreographed to get the conspirators into Florence.

Regardless, the boy made a fine hostage, keeping the Papal Army at arm length.

Of course, the Pope has more tools than an army. Sixtus ordered an interdict upon Florence. In lay-speak, the Pope was ordering all Priests to withhold the Sacraments from Florence and her client cities. He further excommunicated Lorenzo and the Signoria.

An interdict was designed to level pressure on a ruler from the bottom up. A city under Papal Interdict was denied the Source and Summit of Christian Life (the Eucharist), and furthermore, the Sacraments of Baptism, Confession, Last Rites, etc. For the poor of Florence, this was a terrible, painful blow.

It wasn’t a complete blow, because there were plenty of Archbishops and Priests who sided with the Medici, but this pressure would surely build until it blew.

Giovan Battista’s confession, spread through a newfangled device called a printing press, became a powerful arrow in Florence’s quiver.

“Florentine political leaders printed and circulated the confession, in a campaign to denigrate and subvert the interdicts Sixtus has imposed on Florence, Pistoia, and Fiesole…[the Count’s] confession, however, has large shadows; it implicates only the ringleaders; information about the King of Naples and the Duke of Urbino is suppressed; motives are either ignored or made too general; all minor confederates in the web of secrecy are passed over in silence; and the solider himself…keeps hinting that the plot was harebrained.”

April Blood pg. 164-165

The King of Naples, called Ferrante, had a bone to pick with Florence over various diplomatic agreements and was willing to take any excuse to side against the city. Neapolitan and Papal armies began to range the borders of Florence, attacking peasants, hijacking trade routes, and causing general mayhem.

The Pope and his nephew, Girolamo, insisted that peace was impossible until Lorenzo reported to Rome and begged the Holy Father’s forgiveness.

Under Spiritual threat from the Pope and physical threat from Ferrante, Florence was faced with a terrible decision: hand over Lorenzo, or face destruction.

“The crisis peaked and Lorenzo was driven to the wall. Day after day, for months, working on the maestro of the war office Ten, he did nothing but direct policy, sweat out decisions, and write of dictate countless letters. He was desperately overworked. Complaints and murmurings against the regime gained momentum. Trade in wool and silk, the backbone of local industry, had declined sharply. Business travel and employment suffered. The premise of Florentine cloth merchants and banks had been shut down in Rome and southern Italy. To top it all, bread prices had been rising since about 1473. Rioting broke out in the streets of Florence.”

April Blood, pg. 186

Facing riots, raids, and spiritual despair, Lorenzo moved in the only way left to him.

In a courageous act of pure patriotism that struck even his enemies as praiseworthy, Lorenzo left Florence on a diplomatic mission to Naples.

“The move struck contemporaries as sensational, and it has often been the occasion for awe and praise of Lorenzo’s courage, patriotism, genius, luck, and statecraft. None of these can be taken away from him: he was a vastly gifted man…”

April Blood, pg. 188

It difficult to overstate to the modern person just how dangerous a decision this was. Lorenzo was walking into a situation in which he would be totally under the power of the King of Naples, sure, it was under a diplomatic flag, but Ferrante wasn’t the kind of man to let that stop him—he once convinced the Turkish Sultan (a Muslim) to attack Venice (a Christian city) because it was politically convenient to him. If he wanted to bundle up Lorenzo and send him on to Rome and certain death, then he most certainly would have.

But that didn’t happen. Instead, the Neapolitan King got to know Lorenzo, and in getting to know him, began to like him. Concessions were made, but Lorenzo’s charm remained his most impeccable weapon.

And with the slide of a silver tongue and a dash of luck, the Pazzi War came to its end.

That Bitch, Fortune

The hidden character behind the whole bloody scene is a force the medieval and renaissance mind knew all too well.

The modern mind often dismisses the concept of “luck” as mere superstition, but the fact of the matter is that fortune is a lively factor in the movement of the world, even now. I thoroughly believe in the medieval concept of fortune and April Blood does a good job of showing fortune in action.

For all it’s changes, mistakes, and fumbles, Florence was politically ready for a change of leadership. Lorenzo was popular, but he wasn’t that popular.

“Despite the failure…it may be easily argued that the plot was driven by an accurate sense of what was practical and feasible. If Lorenzo had been killed along with Giuliano, or if Archbishop Salviati and Messer Jacopo [de’ Pazzi] had managed to take the government palace…would have forced a change of government in Florence; and change made, to be sure, with the zeal and assistance of hundred of alienated citizens and returned exiles.”

April Blood, pg. 173

It was Dame Fortune who spared Lorenzo that blood-soaked day in April. It was Dame Fortune who turned Ferrante from a foe into a friend. Then, Dame Fortune would come to Lorenzo and Florence’s rescue again:

“Lorenzo’s luck held out. ‘Dame Fortune’ – as many contemporaries would have said – came to his aide less than five months later [after leaving Naples]. Early in August the Turks stormed Otranto in the far south of Italy, killing about 12,000 people and taking another 10,000 into slavery. All at once Ferrante faced a military crisis…and Pope Sixtus was forced to organize action against the infidel…Dropping his hard line against Florence.”

April Blood, pg. 196

Final Thoughts

Sometimes writers put themselves in a jam. They back their characters into a wall and to get them out, they have to rely on a deus ex machine. What a cheap ending! The reader says in their review.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not a fan of cheap endings, but let’s face it—history is full of cheap endings. Lorenzo talked himself out of a war with Naples and the Pope. There was no great last stand, no clash of arms, no falling on swords. Lorenzo won through a series of charming conversations made at quiet dinner parties held in the Naples Branch of the Medici Bank.

The single most important rule of fiction is that it must make sense and real life is under no such obligation.

Still, I think it’s a good idea to think about fortune and the way it affects our lives, and the lives of our characters. Cause and effect must ultimately make room for “Dame Fortune.” When she turns her wheel, we have no choice but to turn into the skid, for good or ill.

April Blood is a great book; it really highlights the tangled web of family, money, and politics that was the lifeblood of Renaissance Florence. I glossed over a lot of details to get to my point, but I hope it encourages you to pick up the book yourself. It’s these real-life examples that I think can really provide a framework for fiction.

As to the Medici and the Pazzi, Machiavelli, I suspect, would call both tyrants. Different sides to the same autocratic coin. He might also say, that sometimes, you get what you deserve and that Fortune is a real bitch.

I wrote a Writer’s Must Read on Machiavelli, check it out here.

Like weird tales? I write my own, you can find them here! You can also follow me on Twitter/X!

Above: Tile floor of the Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Flower (the Duomo) in Florence, Italy.