A General Introduction to the Series.

It’s cliché to say that the Bible is not so much a book as it is a library in a single volume. It contains works of history, law, poetry, prophecy, and even (if you have a Catholic Bible), works like Book of Tobit (Tobias) that has a structure similar to that of a novel. Genre, of course, is a modern invention; the Ancient Hebrews and the original Christians would not have “split” works into neat little categories. And truth be told, the books don’t always fit, like the aforementioned Tobit.

But genre is neither here nor there. My concerns here is the story. And, paradoxically, I lied above. The Bible is a single book in the same way it’s a library. Okay, so perhaps “I lied” isn’t entirely correct either. A better way, I think, to categorize the Bible is with the word Epic. It’s an epic in the same way the Lord of the Rings is epic. Threads from the books before are woven through the entire story, leading up to the epic conclusion of Christ Jesus’ passion, death, and resurrection.

In other words, it’s a Grand Narrative. The stories within the Story are themselves part of the Story. The Story ceases to make sense without these smaller stories. The Grand Narrative is the Word and the Word is the Grand Narrative.

There are many who would disagree with me. Some because I’m thinking to much about it instead of living it. Others because they don’t believe in the Grand Narrative at all. Some will take issue with my choice of Bible, others will discount me entirely because I’m Catholic. Others, because I’m a woman.

All of that is irrelevant. When I peel apart an archetype in Scripture, it isn’t my intention to convert or to undermine or blaspheme. It’s my intention to understand the Story. I want to explore the Library that makes up the bedrock of the Western literary tradition. I want to find the archetypes that prototyped our modern archetypes.

Knowing these archetypes will help us become better writers. Understanding the foundation of Western literature will make us better readers, which in turn, makes us better writers. For those of us who believe, I hope it makes us better believers. For those who don’t believe, I hope it helps you understand why some of us do. Ultimately, this line of thought states that believing in the power of story improves our abilities to read and write.

For my Archetypes of Scripture Series, I will be using multiple Bible translations, mainly the Revised Standard Version: Second Catholic Edition (RSV-2ce); the Revised Standard Version: Catholic Edition (RSV-c); and the Douay-Rheims Version (DRV). I will use them interchangeably, depending on how I feel about the specific translation. Some are prettier than others or use more accurate language or better express what I’m getting at. I will always try to cite my translation.

Jonah, Reluctant Hero

As stated above, the Bible is an epic, meaning that the books make reference to each other, or characters may appear in more than one book. Jonah is first referenced in 2 Kings 14:25. But let’s leave that aside for the moment and focus on the text of the Book of Jonah.

Jonah begins with the Call to Adventure.

1 Now the word of the Lord came to Jonah the son of Amit′tai, saying, 2 “Arise, go to Nin′eveh, that great city, and cry against it; for their wickedness has come up before me.”

[RSV-c Jonah 1:1-2]

Hearing this, Jonah immediately flees.

3 But Jonah rose to flee to Tarshish from the presence of the Lord. He went down to Joppa and found a ship going to Tarshish; so he paid the fare, and went on board, to go with them to Tarshish, away from the presence of the Lord.

[RSV-c Jonah 1:3]

There’s an economy of language common to Scripture and other ancient texts. The action is immediate, there is no time to breath between the Call to Adventure and the Refusal of the Call. The story begins it’s climb and it only has a few stops before it comes to the climax. Likewise, the denouement is as equally swift and in the case of the Book of Jonah, painfully brief.

Let’s take a quick detour to explain what I mean when I use these terms.

The Call to Adventure was coined by Joseph Campbell, likewise was the Refusal to the Call. These phrases are the first and second parts of the Hero’s Journey as outlined in his work The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

The Chosen One is the hero, the protagonist, the one called to the adventure, the one who will complete the quest. The Hero’s Journey can take on multiple forms, usually called Masculine and Feminine. Masculine/Feminine in this context has nothing to do with sex and everything to do with the type of journey; the Masculine is outer, usually marked by self-sacrifice, while the feminine is inner, marked by self-discovery. All good stories incorporate elements of both archetypal journeys.

In the Book of Jonah, Jonah is the Chosen One, he hears the call and he refuses it, choosing to flee to Tarshish instead of going to Nineveh. But why—the reader may ask—does Jonah choose the flee?

The Book of Jonah doesn’t really provide any detail. Like all ancient texts, we must do a little assuming. Often, ancient writers left out details because they assumed their audiences already knew why something was the way it was. Without reading the rest of the Bible, we may be a little confused.

Nineveh was an ancient Assyrian city now located in Mosul of modern-day Iraq. The Book of Jonah takes place in the Eighth Century BC but it was probably written after the Babylonian Captivity (or Exilic Period). This tells us that it probably isn’t meant to be taken historically, although Jonah is a historic figure. The point of this story is to tell a story. It tells the truth in the way all good stories tell the truth.

All this is to say that the Assyrians were more than just Gentiles to the ancient Hebrews, they were their captors and oppressors. Jonah, an Israelite, rightly sees them as the enemies of the Lord. Why would he go to Nineveh to preach repentance? They might actually repent and then Jonah’s enemies will be spared destruction.

So, returning to the narrative, Jonah is on a ship for Tarshish.

4 But the Lord hurled a great wind upon the sea, and there was a mighty tempest on the sea, so that the ship threatened to break up.

[RSV-c Jonah 1:4]

The sailors begin to panic and pray to their various gods. But Jonah, who knows why the storm is happening, doesn’t panic at all. In fact, he’s asleep in the hold, utterly unbothered by the danger. Jonah is exhibiting the main theme of the Book of Jonah, trust in the Lord. The Captain, angrily, says to Jonah: “What do you mean, you sleeper? Arise, call upon your god! Perhaps the god will give a thought to us, that we do not perish.” [RSV-2ce Jonah 1:6]

Lots are cast in order to figure out who’s to blame for the storm. Cleromancy, or the casting of lots has the Greek origin of klêros meaning “lot,” “inheritance,” or even “that which is assigned.” Cleromancy is used 47 times in the Bible, especially as a way to discern the Will of God.

The lot falls upon Jonah and the sailors interrogate him, demanding to know where he’s from and what god he worships. Jonah tells them that he is a Hebrew and that the Lord is his god. He then gives them some advice: “Take me up and throw me into the sea.” [RSV-2ce Jonah 1:12] The sailors hesitate. They don’t want Jonah’s blood on their hands. They try to bring the ship back to land but the storm just gets stronger, ultimately indicating that the Lord wants Jonah as a sacrifice.

14 Therefore they cried to the Lord, “We beseech thee, O Lord, let us not perish for this man’s life, and lay not on us innocent blood; for thou, O Lord, hast done as it pleased thee.” 15 So they took up Jonah and threw him into the sea; and the sea ceased from its raging. 16 Then the men feared the Lord exceedingly, and they offered a sacrifice to the Lord and made vows.

[RSV-c Jonah 1:14-16]

Thus is the inheritance of the Chosen One. For the hero, destiny can be ridiculed, it can be ignored, even fled for a time. But in the end, it will swallow you whole.

In Jonah’s case, he is literally swallowed up by his destiny.

The Lord appoints a fish to swallow Jonah. Famously, Jonah remains in the belly of the fish for three days and three nights, foreshadowing the perfected hero archetype of Jesus Christ.

While in the belly of the fish, Jonah prays to the Lord in a beautiful piece of poetry sometimes called the Psalm of Thanksgiving or Jonah’s Prayer of Deliverance. “But I with the voice of thanksgiving will sacrifice to you; what I have vowed I will pay. Deliverance belongs to the Lord!” [RSV-2ce Jonah 2:9]

Jonah, now having vowed to do as he’s been called to do, is unceremoniously vomited up onto dry land.

This is the lynchpin of the Reluctant Hero’s arc. After fleeing the adventure, the hero is always caught up by it. The way the snare is set is how great stories differentiate and become varied. Perhaps a loved one is killed? or an unrefusable offer is made? or the character simply makes the choice to stop ignoring the call? Regardless of method, the Reluctant Hero is made to finally embrace their destiny and, most importantly, they embrace the consequences of that destiny.

This archetype, I believe, is most easily seen in the Lord of the Rings. Hobbits are not the adventurous type, but when fate comes asking questions in the Shire, Frodo is forced to flee where he is quickly caught up in events much larger than himself. He eventually accepts his fate, and to contrast with Jonah, he makes the choice to take the Ring, not to please anyone, but because it is the right thing to do. He knows the journey will be fraught with difficultly and that he may lose a part of himself, or even loose his life. But Frodo is the Ringbearer. In a series about reluctant Chosen Ones, Frodo is preeminent.

Now back on dry land, the Lord tells Jonah a second time, “go to Nineveh.” This time, Jonah goes. Nineveh is a great city, according to the Book of Jonah, it’s “three day’s journey in breadth.” Jonah walks one day’s journey into the city and cries, saying, in forty days’ time, Nineveh will be overthrown.

Miraculously, the people of Nineveh believe him. They proclaim a fast and put on sackcloth. The message makes its way to the king of the city, who rises from his throne, puts on sackcloth and sits in ashes. He decrees that all men and their animals will fast, taking neither food or water. He orders them to wear sackcloth and to cry out to God and turn from their evil ways.

Take a moment to imagine how funny sheep, cows, chickens, and other animal would look in sackcloth. This image, I believe, is purposefully amusing and marks a deliberate choice of the author to plant his tongue in is cheek.

The Lord sees that people of Nineveh (and their animals) repent, and “God repented of the evil which he had said he would do to them; and he did not do it.” [RSV-2ce Jonah 3:10]

The fourth and final chapter of Jonah speeds towards the end just as swiftly as the first sped to the action. Jonah, angry because the Ninevites repented and were spared destruction, prays to the Lord: “I pray thee, Lord, is not this what I said when I was yet in my country? That is why I made haste to flee to Tarshish; for I knew that thou art a gracious God and merciful, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love, and repentest of evil. Therefore now, O Lord, take my life from me, I beseech thee, for it is better for me to die than to live.” [RVS-c Jonah 4:2-3]

Jonah is quite the stubborn fool and, in a sense, like a teenager. Angry that his enemies have been spared, he declares that he’d rather be dead. “I’d rather be dead than have a father like you!” the Lord answers in trademark laconicism; “Do you do well to be angry?” [RSV-2ce 4:4]

Still mad, Jonah leaves Nineveh and pitches a tent east of the city in order to watch Nineveh. There is nothing that betrays Jonah’s thoughts, but perhaps he hopes that the Ninevites were just putting it on for his benefit and they’ll be destroyed not just for being idolatrous oppressors, but because they’re liars too.

Instead, the Lord makes a plant grow over Jonah so that he has some shade from the heat of the sun. This makes Jonah happy, despite his attitude, despite his unwillingness to attend properly to the call, the Lord still cares for Jonah. But, like any good parent, this is a teaching moment. The next day, the Lord sends a worm to wither the plant. The Lord then makes a hot wind and makes the sun beat upon Jonah.

Disappointed, and now, hot and tired, Jonah again declares that it would better to be dead.

But God said to Jonah, “Do you do well to be angry for the plant?”[d] And he said, “I do well to be angry, angry enough to die.” 10 And the Lord said, “You pity the plant,[e] for which you did not labor, nor did you make it grow, which came into being in a night, and perished in a night. 11 And should not I pity Nin′eveh, that great city, in which there are more than a hundred and twenty thousand persons who do not know their right hand from their left, and also much cattle?”

[RSV-c Jonah 4:9-11]

And that’s how the Book of Jonah ends. Of course, there’s still plenty to break down here. For one, the journey almost doesn’t seem complete. Is Jonah a better person? Does he understand what the Lord was trying to do?

I think the best way to examine this ending is to see it as an imperfect blend of both the masculine and feminine journey. We aren’t told that a profound inner change came upon Jonah, its barely even implied. But, assuming that he was changed, Jonah has undergone the feminine journey which is characterized by a deep, inner expansion of the self. Jonah has learned something about his god. A facete of the Lord is revealed to Jonah, a piece, that frankly, isn’t always easy to find in the Old Testament.

“Should I not pity Nineveh?” God asks and for the Christian this is clearly the voice of God the Son.

Knowing this, we can see how Jonah is also participating in the masculine journey. He has learned something new that will aide his people in the future. More so, he has confirmed a piece of ancient knowledge already known but forgotten in the turmoil of the Exilic Period.

As I said above, the Book of Jonah was probably written after the Babylonian Captivity. The Hebrews needed to relearn the mercy of the Lord. Yes, that’s right. I’m arguing that the text itself is the secret knowledge found at the center of the masculine journey. That means that every reader (at every time, anywhere, etc) is participating in the Hero’s Journey.

Writing and reading are participatory. You should read like you’ve heard the call to adventure and you should write like you’re calling the reader to adventure.

Never underestimate the power of these tropes. That word has been getting a lot of bad press lately, but there’s a reason why these foundational stories are so powerful. Breaking them down or imploding them can be useful for a time, but ultimately, when embraced, these tropes underline the journey of the human soul, from life to death and maybe even beyond.

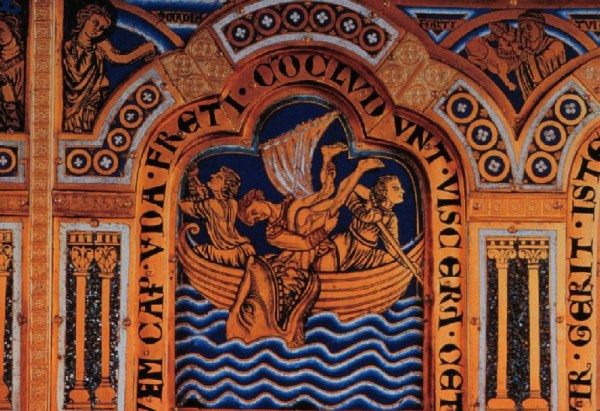

Above: Jonah and the Whale, a fraction of the Verdun Altar at the Klosterneuburg Monastery in Austria. Nicholas of Verdun (1130 – 1205). Enamel on metalwork (Champlevé). Housed in the Chapel of St. Leopold, Klosterneuburg Monastery, Austria.