Conan casts a mighty shadow over the swords and sorcery genre. You might even say, Conan is the genre. At the very least, he is the gold standard and all sword and sorcery fare is measured against the Cimmerian, regardless of the fairness of it.

The half-clad, sword-wielding barbarian is the trope de jour in all things swords and sorcery. From movies, to short story collections, to heavy metal music—if it’s swords and sorcery, it’s got buxom ladies, evil wizards, and loincloth bedecked barbarians.

This isn’t a bad thing. I like tropes, I think they’re useful—good, even! And this trope is one of my favorites. I love a good sword-swinging savage man, bare-chested, blood covered, roaring insults against cowards and foes alike.

And if you like this trope too, Conan is your man. But, he’s also wily, cunning, quiet, pensive, chivalric, deceitful, womanizing, loyal, sneaky, brash—in other words, he’s complex.

Now, complex does not mean he completes a full “modern” character arc—in fact, he wouldn’t be Conan if he “changed” at the end of his tales.

“The Pulp Structure” as I call it, is about a character facing an obstacle or series of obstacles be they physical, mental, or both and overcoming those challenges. The story is found in the way they overcome the contest. Most importantly, they need to surmount the obstacle with their character or morality or ideology intact.

This resistance to change serves two purposes, it preserves the integrity of the kind of character that Conan is. It is also the mechanism that allowed Robert Howard to write Conan into all sorts of situations. The fun of a Conan story is in how Conan solves the problem before him.

“Hither came Conan, the Cimmerian, black-haired, sullen-eyed, sword in hand, a thief, a reaver, a slayer, with gigantic melancholies and gigantic mirth, to tread the jeweled thrones of the Earth under his sandalled feet.”

-The Phoenix on the Sword

This is Conan, a savage from the wastes of Cimmeria. A mercenary and robber. A man who has known great joy and even greater sadness. Impudent, knavish—he scoffs at kings and peasants alike. He lives, he burns with life, he loves and slays and is content. Plunder is seized and spent just as quickly—his philosophy, if a man like Conan has one, is this:

“I think of Life! The dead are dead, and what has passed is done! I have a ship and a fighting crew and a girl with lips like wine, and that’s all I ever asked. Lick your wounds bullies, and break out a cask of ale. You’re going to work ship as she never was worked before. Dance and sing while you buckle to it, damn you! To the devil with empty seas! We’re bound for waters where the seaports are fat and the merchant ships are crammed with plunder!”

-The Pool of the Black One

Conan is not a man who goes out of his way to protect the weak. In fact, he doesn’t have a lot of respect or understanding for the weak and the poor.

By his estimation, the poor ought to get strong and rob the rich. The life of man is warfare, so men ought to take up sword and war. The strong will grow stronger because they are strong and the weak will die, because they are weak.

In this way, Conan is pure pagan. He would hear the words of Jesus “blessed are the poor” and sneer and ask how man is meant to eat a blessing.

This is best exemplified by the shadowy, utterly absent, cold and grim, god of the Cimmerians—Crom.

“Their chief is Crom. He dwells on a great mountain. What use to call on him? Little he cares if men live or die. Better to be silent than to call his attention to you; he will send you dooms, not fortune! He is grim and loveless, but at birth he breathes power to strive and slay into a man’s soul. What else shall men ask of the gods?”

-The Queen of the Black Coast

Conan’s fatalism is more Norse than it is Roman. His grim god’s attention promises doom, but despite that he seems to call out Crom’s name as if tempting fate, daring, maybe even demanding that promised doom so he might conquer it.

The Hyborian Age, the fictional pre-history setting of Howard’s Conan stories is awash in pagan fatalism. There is Bel, the god of Thieves; Mitra, the most widely worshiped and beloved of the gods; Set, the snake god of the Stygians who demands human sacrifice; the mysterious Asura. The good ones, if there are good ones, are Bel, Mitra, and Asura.

Conan does not call on any of them. Nor does he seem to care for their cults and practices. He has little regard for “blasphemy” and would do battle with a god if it suited him. The Priests of Asura have aided Conan in his journey, and Mitra has aided others in finding Conan’s help. He has spurned Set in a more physical way—slaying his children and confounding his priests.

For the average people of this mythical age, there appears to be little hope. This fatalistic caste system, where the strong prey on the weak, makes slavery, wanton cruelty, and human sacrifice the order of the day.

Power is all that matters, and those who don’t have it, live and serve at the pleasure of those who do.

Women are the particular victims of this system. Although Howard never spells out exactly what occurs in the flesh markets, harems, and pleasure palaces of the civilized nations, it is easily discernable to any but the most naïve of readers.

“…her worst oppressor had been a man the world called civilized.”

-Iron Shadows in the Moon

The tension between civilization and savagery is the red-hot pulse of the Conan stories. Howard does not hide what side he comes down on—barbarism is the superior. What Howard really appears to be doing is showing the ultimate end of degenerated civilizations. Rome degenerated and fell to “barbarian” incursions. The same fate befalls Aquilonia.

The difference, of course, is Conan.

He bucks against the spirit of fatalism. He forges his own path, mocks the gods. He has no need for the rules of civilization or savagery. If he is a barbarian, then I suspect we’d all wish to be barbarians.

“We do not sell our children.”

-Iron Shadows in the Moon

Conan says to a woman sold into sexual slavery by her own father. He’s never forced a woman against her consent, bought a human being, or forced a heavy tax burden on his people. He is a thing apart. Perhaps the only true example of rugged individualism that has and even will be.

Conan is a renewing force; an infusion of fresh blood into a sickly man. He does not change, but all who meet him are changed. Slaves are freed, spines are steeled, villains are slain. In a bizarre, round-about way Conan is a liberator. Whether physically, or spiritually, Conan slaps sense into those around him, especially those who read him.

If you’re tired of tepid modern fantasy with it’s warmed-over Tolkienian platitudes, or handwringing, “grimdark” antiheroes; Conan might be the barbarian for you. Think of life! Think of rich red meat and stinging wine, think of passion and the flash of crimson blades, and be contented!

“Oh, soul of mine, born out of shadowed hills,

To clouds and winds and ghosts that shun the sun,

How many deaths shall serve to break at last

This heritage which wraps me in the grey

Apparel of ghosts? I search my heart and find

Cimmeria, land of Darkness and the Night.”

-Cimmeria

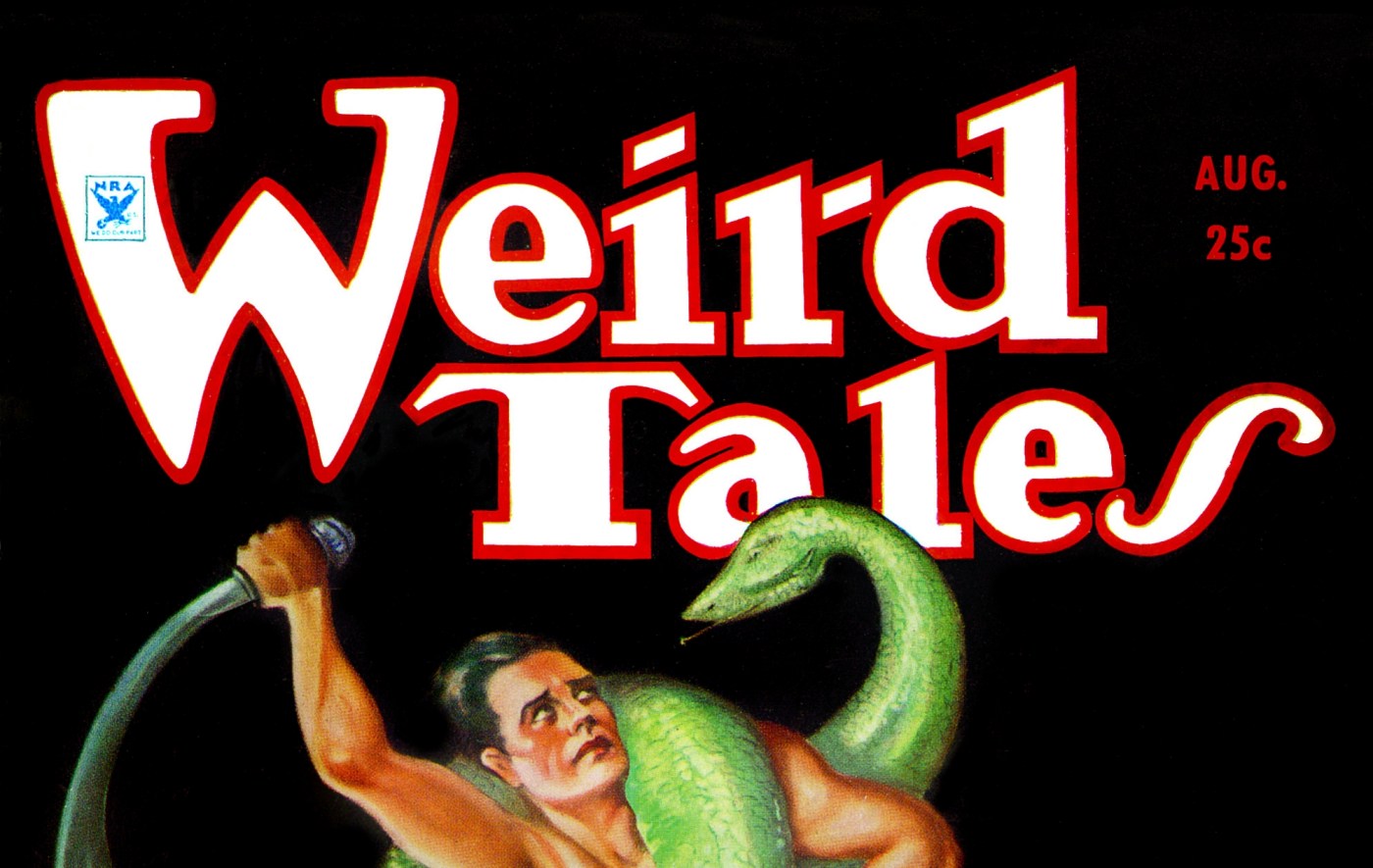

Above: A section from the August 1934 cover of Weird Tales featuring Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Cimmerian in The Devil in Iron.

I write my own weird tales, check them out here and follow me on X/Twitter.